Mexico Eases Requirements for US-Schooled Children

|

|

| “The main problem that migrants face when they try to get school services, is the lack of documents, and the requirement that they get the apostille,” the Education Department said in a press statement. | |

|

|

exico on Monday enacted a measure meant to help hundreds of thousands of young migrants who have returned from the United States, dropping a requirement that they provide government-certified, translated copies of foreign school records in order to study in Mexico.

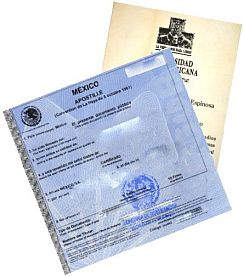

Mexico had required records be certified with a seal known as an apostille and be translated by a certified translator in Mexico.

The costly and cumbersome process had discouraged hundreds of thousands of returning migrant children from going to school in Mexico, or meant they could only audit courses without official recognition. Hundreds of thousands of children have returned to Mexico, mainly from the United States, after their parents were deported or chose to return.

The Education Department published changes to the rules on Monday, saying its goal was to make education more accessible. The department also dropped the certified-translation requirements. “The main problem that migrants face when they try to get school services, is the lack of documents, and the requirement that they get the apostille,” the Education Department said in a press statement. The apostille is a seal issued by state or federal agencies to authenticate government documents, including school records.

|

The seal costs only about $8 per document, but getting schools to express-mail documents to apostille offices in the United States, and then on to recipients in Mexico, from outside the country, and then getting them translated, can run into hundreds of dollars.Berenice Valdez, the public policy coordinator for the non-government Institute of Women in Migration, told of one returning migrant in the central state of Puebla who earns less than $100 per month and has three children who need to authenticate their U.S. school documents. The woman couldn’t even afford to travel to the state capital to start the process.

“It is a very big problem that prevents access to education for many children,” Valdez said. The institute estimates that about 307,000 foreign-born children were studying in Mexican schools, almost 290,000 of whom were born in the United States.

The number of Mexican-born returning migrant children may be as large or larger.

Many times, returning migrant children are allowed into schools to audit classes, but can’t get official school certificates at the end of the year.

“Our task is to guarantee equal access to educational services… for migrants, who are an extremely vulnerable sector of the population,” said Assistant Education Secretary Javier Trevino. “Our goal is to make sure that access, retention & promotion in the educational system is based only on children’s academic performance.”

Beyond just academics, not being able to get into school makes life more difficult for children already struggling to adjust to a culture and language many of them know little about after years in the United States.

“It had a very strong emotional impact” on migrant children, Valdez noted, “because education is an important part of their integration.”

Why the rules weren’t changed earlier, despite years of pressure from migrant parents, isn’t clear.

“It was bureaucratic inertia,” said Valdez. “Nobody wanted to take the initiative.”

But it appears that other identity documents needed to get health care at public hospitals and clinics may still need to be translated and be certified with an apostille.